From Isfahan to Kabul: Inside Iran’s Mass Deportation of Afghan Refugees

Originally published at Alhurra

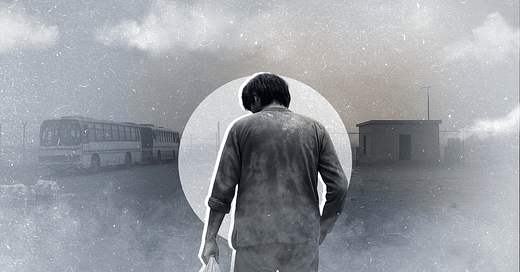

In the sweltering heat along the Iran-Afghanistan border, a young Afghan man named Abdullah was transported from the city of Isfahan to the Dogharoun border crossing in a nonstop 13-hour journey.

“They didn’t let us buy water or food. The heat was unbearable,” he said, speaking from a modest hotel in Kabul. “Now I’m trying to get an ID and passport!”

Behind this painful journey lies a bigger story: a harsh deportation campaign that Iran is waging against millions of Afghan refugees.

War and Deportation in the Name of Security

After the outbreak of war between Iran and Israel in June, Tehran launched a mass deportation campaign targeting Afghan refugees.

Iranian authorities arrested many of them, accusing some of espionage and collaboration with Israel.

Humaira Qaderi, Afghan author and fellow at Harvard's Radcliffe Institute, told Alhurra that the Iranian government and media began referring to Afghan migrants as “spies.”

“The rhetoric shifted from blaming Afghan refugees for burdening the economy before the war to accusing them of threatening national security afterward,” says Mitra Naash, assistant professor and director of the “Forced Migration Initiative” at the University of Washington.

“This narrative was used to justify mass expulsions,” says Qader Habib, an expert on Afghan affairs and director of the Afghan service at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

More than that, the Norway-based Hengaw Organization for Human Rights reported that Iranian authorities executed 10 Afghans during the month of June alone.

The organization said the charges included murder, drug trafficking, rape, and armed robbery, but also religious and political offenses.

Since June 13—the day the war began—the pace of deportations increased dramatically. Over 300,000 Afghans were expelled in just 12 days. In June alone, more than 450,000 Afghans returned from Iran, according to the United Nations.

“Deportation rates jumped from a few thousand a day to 40,000 daily,” says Qader Habib.

“This is one of the largest forced return operations in the world.”

The young refugee we spoke to said, “I was detained three times, and on the last one, they deported me. We were mistreated and insulted… they put us on buses and didn’t allow us to stop the entire way.”

Even Before the War

Even before the war erupted in June 2025, Iran had begun intensifying its deportations. In 2024, around 750,000 Afghans were expelled. In May, Tehran announced its goal to deport 2 million undocumented Afghans by July.

Iran hosts more than 6 million Afghan refugees, who have fled decades of war in their home country.

Qader Habib says the country’s economic crisis has pushed the authorities to blame Afghan refugees for Iran’s deteriorating conditions—pointing to rising inflation, unemployment, and heavy sanctions that have crippled the Iranian economy.

He told Alhurra: “The authorities promoted the idea that Afghan migrants consume resources and compete with locals for jobs.”

Habib rejects these claims, saying that most migrants work in difficult jobs that Iranians don’t want—at low wages.

“I used to work in a brick factory in Isfahan,” says Abdullah, who was given this pseudonym for security reasons.

The young Afghan had lived in Iran for four years.

As the economic crisis worsened, hostility toward Afghans intensified in Iranian society. On social media, the hashtag “Deporting Afghans is a National Demand” regularly trended.

“In fact, in the lead-up to Iran’s 2024 presidential election, several candidates openly blamed Afghan refugees and held them responsible for the country’s social and economic challenges,” says Mitra Naash.

“The general atmosphere became increasingly hostile… Afghans were portrayed as a burden and a threat,” Habib confirms.

He adds: “Social media and the press played a big role in this shift.”

Two Allies Without Real Allies

After the war, deportation campaigns reached unprecedented levels.

But these campaigns don’t seem to stem solely from Iran’s internal crisis. In fact, they also reflect persistent tensions between Iran and Afghanistan—driven by long-standing disputes over water, trade, and borders.

In this context, the refugee issue appears to be a pressure card Tehran is using against the Taliban.

Even so, Habib doesn’t believe relations are genuinely tense. “The Taliban, isolated internationally, are keen to maintain good relations with Iran and lack any real leverage,” he says.

“Due to its lack of diplomatic recognition, the Taliban see stable relations with neighboring countries like Iran as politically important.”

Iran itself has few remaining allies. The Taliban may be one of the few left.

In January, Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi visited Kabul and declared that “a new chapter” had opened in relations with the Taliban.

It was also notable that Araghchi criticized what he called “Taliban-phobia,” urging people not to view the group as an enemy.

That came four years after the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan. Iran recognized their de facto authority but never officially recognized the Taliban government.

For those four years, Tehran consistently demanded a government inclusive of all Afghan factions. But that demand disappeared after Araghchi’s visit.

Both sides seemed to need each other. And “it doesn’t seem that the refugee issue is causing any serious tension between them,” says Qader Habib.

A Crisis at the Border

The humanitarian toll is devastating. Deported refugees arrive at the border exhausted, dehydrated, and often with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

“We had nothing,” the young Afghan says. “At the border, they kept us under the scorching sun. They prioritized families.”

On the Afghan side, men were transported in shipping containers to Herat, while families were taken by bus.

“I didn’t board those containers. It was too hot—we might have died inside before reaching Herat.”

International organizations like the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Red Cross provide only minimal assistance. IOM says it can only reach 10% of those in need. The UNHCR office in Afghanistan is severely underfunded—having secured less than a third of its 2025 budget.

“Returnees lack food, shelter, and health services,” Habib explains. “Women and children are especially vulnerable.”

Humaira Qaderi also highlights a crucial issue: “Many Afghan girls who were deported will face a harsh reality. They grew up and were educated in Iran, but upon returning, they’ll be denied schooling and lose their chance to continue their education,” she tells Alhurra.

Habib adds that returnees who belong to the Hazara Shia minority, civil society activists, former army officers, government employees, women’s rights activists, and journalists are all at risk of Taliban retaliation upon return.

Taliban’s Inability to Cope

Facilities on the Afghan side of the border—especially in Herat—are operating beyond capacity. Under a Taliban government that is financially broke and politically isolated, the response has been woefully inadequate.

“The Afghan authorities lack the capacity to absorb this number of returnees,” says Habib. “Afghanistan is already undergoing economic collapse.”

This deteriorating situation could trigger waves of internal displacement within Afghanistan—and possibly spark a new wave of migration abroad, perhaps toward Europe.

But despite UN appeals to halt forced deportations and for donor countries to intervene urgently, the international response remains limited.

In Kabul, the young Afghan man awaits a passport. “We have nothing here,” he says. “In Iran, at least we had something to do… I’ll try to get a visa and go back to Iran.”

Caught between two fires, the Afghan refugee remains trapped in an endless cycle: unwanted in Iran, and forsaken in his homeland.